My dad says the only way to eat a watermelon is to cut out its heart. To crack it open and discard the bits even remotely close to the rind. He disclosed this to me this past summer while we were on vacation in Montana. In a hunter’s lodge visiting my wife's family. We coordinated this grand vacation as a celebration. After we were all vaccinated and itching to leave our homes. My dad approached me on the penultimate day of our stay. I clocked him amidst the amplified voices that bounced around a lodge with metal walls and an open floor plan.

"¿Y tu eres que escogio la sandia?"

"Yeah, I picked it. ¿Porque? It's not good, huh? I coulda swore it would be."

He laughed. "No. Es cruda. I know you picked it out because it's no good."

"Yeah, yeah," I said as I let out a little shrug. I wanted to explain how long I’d dug through the box of watermelons at the store. How I had googled the steps to find the absolute perfect melon from the bunch. Pronounced yellow spot. Distinct webbing. I held my phone in one hand while I batted away the melons that didn't fit the bill with the other. I did not tell my dad any of this for fear of more ribbing. I took my dad’s teasing in stride. I was just happy that he was there to dish out the ribbing. That he and my mom had survived their bouts with COVID.

COVID-19 felt like a behemoth that contradicted itself at every turn. It was at once slow moving and blindingly fast. A lumbering slasher villain popping up behind you on a call. Like the call where my mom told me my parents had caught it. My breath hitched in my throat when she revealed my dad had it bad. The next week my job held the first of many virtual staff meetings. "How have folks been coping?" one Zoom square asked the others.

"You know. It's hard. I felt like I've binge watched all that I can!" Another square replied to a chorus of tinny laughs from my laptop speakers. I refrained from sharing the thought swirling in my brain. We're talking about this when I'm afraid this meat factory is going to consume my family?

My dad worked at a meat processing plant deemed essential during the pandemic. They jammed a swab in my dad's nose and sent him home on Friday. An automated call greeted him Sunday evening telling him that his results were negative (They weren’t.), and that they expected him the next morning. He couldn't go in even if he’d wanted to. He’d stand up from his recliner only to steady himself against the wall after a few steps, breathless. At one point he turned to my mom and said, "We're going to die from this. In this house. Alone."

Words cannot convey how angry I was at the plant for that automated phone call. At a society that abandons and exploits us. I had family members in a factory on the other side of the state. Where supervisors had a betting pool on which of their workers would catch COVID first. When my mom called, it was the most alone I’ve ever felt. Not because it was four months and counting in isolation. Not because my parents were upset that my wife and I declined to visit during the holidays. But because it felt inevitable. The way we tried, but it still rocked my family the way it did.

But on the other side of it, the families were bustling on the last day of our stay in Montana. My dad brandished a watermelon he had acquired that morning. He picked it out with a method he has yet to reveal to me. One that I bet does not involve smart phones or Google. Folks circled my dad, shoulder to shoulder, necks craned from behind the huddle as he took out a pocketknife. After wiping the blade on his shirt, he cut into it, taking care not to plunge the knife fully into the fruit. He jostled and cracked off pieces that he chucked into a nearby bin.

What was left was a picture of a watermelon I hadn’t seen before. It looked like a heart, red and exposed from the pieces my dad ripped from it. My father cradled the bottom of the sandia in his arms as he cut off pieces for the crowd. We grabbed them with our bare hands. To eat quick before the juices ran down our arms onto the floor. My dad smiled as others in the lodge clambered over to get a piece for themselves. Kids snaked through the legs of adults and held up grubby hands to get their own piece. It was one of the best watermelons I've tasted. After all, it's the only way to eat it.

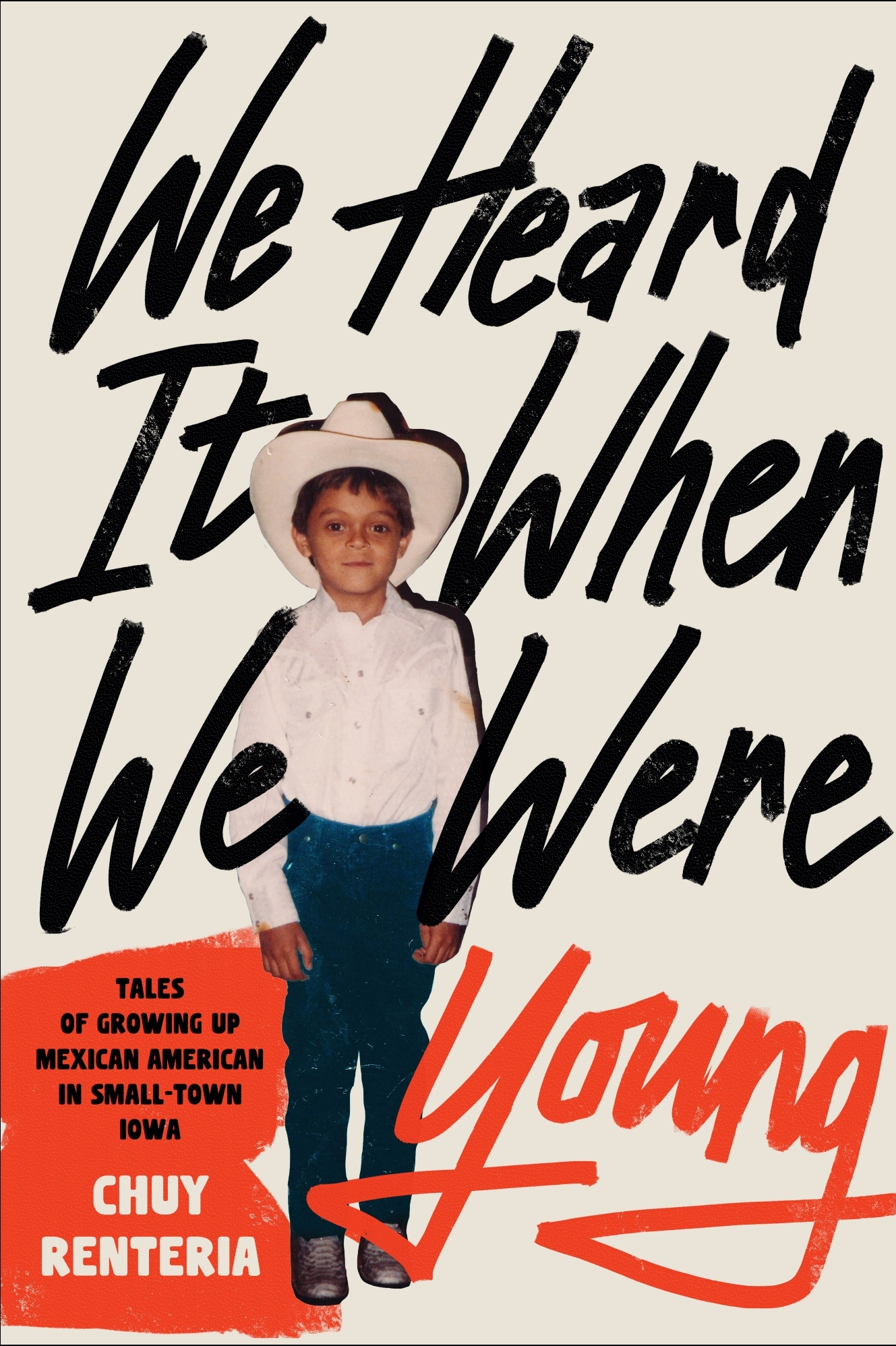

Jesus “Chuy” Renteria is from West Liberty—Iowa’s first majority hispanic town. Chuy’s writing explores the spaces between cultures. Their memoir, “We Heard it When We Were Young,” was released in 2021 with The University of Iowa Press. He spends his free time with his wife Darcy and daughter Marisol Alana.

Mary Swander’s Emerging Voices, webbed into the Iowa Writers Collaborative, spotlights diverse writers on current topics. Please subscribe to this page. Paid subscriptions help pay the writers.

Please support my colleagues at the Iowa Writers Collaborative. I recommend their pages!

You're welcome. Thanks for doing the piece. I hope you'll write more for me for this page. Everyone loved your commentary!

Beautiful.