The Unfinished Sweater

By Susan M. Strawn

The National World War II Museum

New Orleans, Louisiana, 2007

“Are there any questions?”

The director of the National World War II Museum in New Orleans had concluded our exhausting tour of battles and generals, horrors and heroism, fearsome tolls on humanity.

My question seemed anticlimactic.

“What about the Home Front knitters?” I asked, mindful of wartime knitters who had turned out staggering numbers of stockings, sweaters, and such that kept troops warm and closer to home. “Do you have wartime knitting in your collection?”

“Yes, we do,” he said. “And I think the knitting is still out on the tables back in collections. We got it out for a knitting guild that met here. Would you like to see it?”

This is too good to be true, I thought.

“There’s an unfinished sweater,” he said. “A woman was knitting a sweater, one of those Red Cross sweaters, and the minute she heard the war in Europe was over, she stopped knitting.” I hurried to keep up with him as we walked through a maze of hallways toward collections storage.

“She was a saver,” he added. “After she died, her children found her unfinished sweater and Red Cross uniform stashed in a chest. They donated them to our museum.”

In the storage area, knitted helmets, a vest, muffler, and the unfinished sweater lay on worktables covered with padded muslin. Rows of tall metal shelves held hundreds of archival gray boxes, each with artifacts protected by acid-free tissue paper. Military uniforms covered with muslin sleeves on padded hangers hung on racks. Metal cabinets, tightly closed, secured larger, three-dimensional objects, and flat file drawers held smaller pieces like medals and ribbons.

I felt at home in this quiet place behind the scenes, a place of caring and reflection where few others had reason to venture. I liked time alone with curators and librarians in archives, special collections, and museum storage rooms. The curator was folding a knitted muffler with archival tissue.

“Susan’s here with the textile conference,” the director told her. “She teaches history of dress at a university.” I appreciated his lending my presence a bit of weight.

“Do you still have the wedding dress out, the one made from a silk parachute?” He glanced toward me and smiled. That was quite a prize for their collection. The curator held up the gown, delicate and beautifully sewn. The slim waist, generous train, gathered and puffy sleeves shouted 1940s. She shared the gown’s history, which I have forgotten. My mind was on the unfinished sweater.

“Susan studies American knitting,” said the director. “Could you show her the unfinished sweater?”

“That would be Mrs. Wardi Keter Kalil,” said the curator. “Her sweater’s over here with her knitting pattern books.”

Ah, the thread of a story.

I was not in New Orleans for research. I was attending a textile conference and volunteering at another museum, one of the victims of catastrophic flooding from Hurricane Katrina one year earlier. In a pinch, I penciled my research notes on the back of my hotel receipt and borrowed a camera from a colleague.

The curator handed me gloves. Curatorial rules were clear: “Wear gloves to handle cloth. Remove the gloves but wash your hands before you touch paper. Take notes in pencil. Ask me before you touch anything else.”

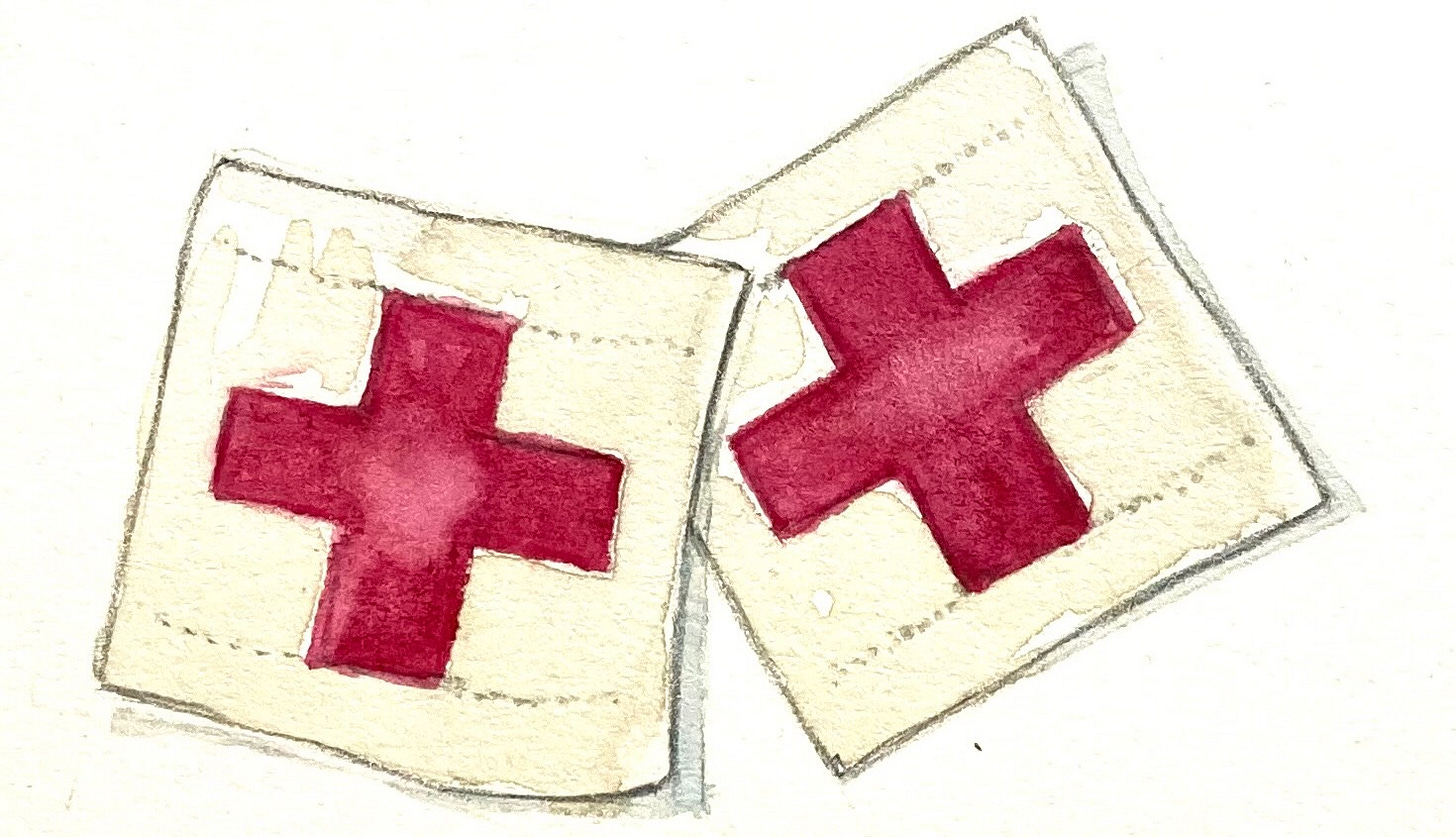

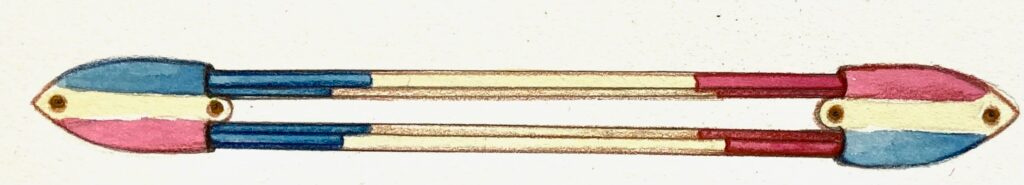

The unfinished sweater lay on a table among other wartime knits. A woven label supplied by the Red Cross was sewn onto a knitted helmet (head and neck covering with face opening). The American Red Cross had standardized vast quantities of olive-drab and navy-blue wool yarn and had printed knitting patterns for helmets, sweaters, vests, socks, mufflers, fingerless mitts, and other comfort items distributed to the troops. The greatest need was for socks, quickly worn out, seldom saved. Knitters could work with red, white, and blue knitting needles supplied by the Red Cross and other relief organizations.

The Red Cross and Navy League coordinated distribution of the prodigious output of knitting donated by civilian volunteers. The November 24, 1941, issue of Life magazine advised, “To the great American question ‘What can I do to help the war effort?’ the commonest answer yet found is ‘knit.’” First Lady and “First Knitter” Eleanor Roosevelt, a prolific knitter, was photographed carrying her knitting bag on patriotic travel across the nation. When a speaker complained that people had been knitting during her lecture, a New York Times columnist suggested the correct concern should have been “whether any speaking should be permitted while women are knitting.”

I lifted, gently, the unfinished sweater. It felt seriously warm, sturdy, wooly. Mrs. Kalil was in that sweater.

“Hello, Mrs. Kalil,” I said, admiring her even stitches and gauge. “You were a very good knitter.” I may have said that out loud. If so, the curator understood. The silence of objects can frustrate those who hold the past in their hands. If only you could talk, I thought.

Mrs. Kalil had completed the front and back of the sweater in one piece. She had knit both sleeves nearly to armhole length before slipping the stitches off her needles and onto a metal stitch holder. Many hours of knitting were in that unfinished sweater.

I searched page by page through Mrs. Kalil’s copy of Practical, Warm Hand Knits for Service Men, a Montgomery Ward pattern book. Lines of pencil marks counted rows she had completed for the sleeveless sweater pattern, though she was adding sleeves. Marginalia—notes and sketches in the margins of knitting patterns—brings me close to the knitter.

The curator handed me a folder with Mrs. Kalil’s awards for wartime service. The American National Red Cross recognized her “meritorious personal service,” and the State Defense Council of Florida awarded her a Certificate of Recognition for “faithful, patriotic” volunteer service on behalf of Civilian Defense. She received both a Citation and Certificate of Recognition from the United States Treasury Department and Florida War Finance Committee. The United Service Organizations (USO) and National Catholic Community Service recognized her for “Distinguished Service to the Nation.” On her United States Citizens Service Corps award of membership “by reason of service to her country,” the printed word “his” had been crossed out, and “her” typed above.

“Would you like me to let Mrs. Kalil’s daughter know how to contact you?” asked the director. “She was the donor. I think she’d be interested in talking with you about her mother.”

“Oh, yes!” I assured him, digging out my university card from the conference tote bag. Mrs. Kalil’s daughter called shortly after I returned home.

“My mother, Wardi Keter, was the oldest of nine siblings,” her daughter told me. “She was born in 1909 to Syrian immigrant parents living in Lowell, Massachusetts. When she was seventeen, her own mother died, and she became more mother than sister to her three surviving brothers and four sisters.”

She remembered her grandfather for his hard work and devotion to his country. He was proud that “he never took a dime from Uncle Sam.” He supported his family selling produce “morning to night” from a truck, then invested in rental property and in 1925 moved his family to West Palm Beach, Florida.

In 1928, Wardi Keter married Laba Kalil, a Lebanese immigrant. They had six children, three girls and three boys. Two of Mrs. Kalil’s brothers, Thomas and John, were killed in action in Europe. She wrote President Roosevelt to request compassionate transfer from Europe to the United States for her last brother, Guy. She was uncertain that Guy would agree to the request, but he did return and lived until 1978.

“She was a prolific knitter before the war,” said Mrs. Kalil’s daughter. She recalled her mother knitting mother-and-daughter sweaters and a two-piece suit. In 1941, after she began knitting for servicemen and women, she also knit a patriotic red, white, and blue sweater for her.

“My mother brought soldiers home from the USO for family dinners. I have many original letters from the USO thanking her for cakes, pies, and serving as receptionist for evenings entertaining the troops.” The boys in the family collected newspapers, and her brother won the competition for the paper drive. Mrs. Kalil taught her daughters to knit simple garter stitch mufflers.

On Friday, May 8, 1945, Mrs. Kalil learned that Germany and Italy had surrendered, marking the end of the war in Europe. She would never finish the sweater on her needles for reasons both personal and political. After her death in 1999, at the age of ninety, her children discovered their mother had saved her unfinished sweater, Red Cross uniform, and wartime certificates.

Sadly, my own grandmother was not a saver. A Danish immigrant and superb knitter who had first placed knitting needles into my small hands, she knit for the Red Cross during World War II. She never talked about that. Only by happenstance, I learned of her wartime knitting from a notice in her hometown newspaper:

Receives Red Cross Yarn

Mrs. Thea P. Moseman, local Red Cross knitting chairman, has received a shipment

of 50 pounds of yarn. She urges all women who are interested in knitting for the

Red Cross to call for yarn at her home.

Grandmother left no other threads of her knitting story for me to follow. What has been lost to history and to me?

Fortunately, Mrs. Kalil was a saver.

Her daughter saved and donated the threads of her story to The National World War II Museum.

“An Unfinished Sweater: The Wartime Knitting of Wardi Keter Kalil” appeared in the January/February 2009 issue of PieceWork magazine, pages 30-32.

“It brought tears to my eyes as I read about my mom and all the things she did to help in the war effort,” wrote her daughter.

“I’ll save it for our grandchildren.”

Susan Strawn researches and writes stories she finds held in cloth and clothing.

She is the author of Knitting America: A Glorious History from Warm Socks to High Art (Voyageur Press, 2007), a cultural history of hand knitting, and of more than 50 published articles, many on the history of American knitting. She is a frequent contributor to PieceWork, a magazine of history and needlework.

Her current project is a memoir, Loopy: How Knitting Saved My Mind and Opened Doors to the World. Read other work by Strawn on Substack. Her website is susanstrawn.com. She lives on Bainbridge Island, Washington.

This piece was reprinted from The Blazing Star Journal, an AgArts publication.

The Iowa Writers’ Collaborative is hosting its annual holiday party Wednesday, Dec. 17, from 7-10 p.m. at The Harkin Institute, 2800 University Ave., Des Moines, on the campus of Drake University.

Paid subscribers to the newsletters of Collaborative members are invited to attend for free. The cost for non-members is $35 per person.

This is a good opportunity to meet writers from the Collaborative and enjoy some holiday cheer.

You can RSVP here.

What a heart-warming story. These knits are every bit a part of the history of WWII, and it's wonderful that pieces from that time are in the museum's collections. When I think of what future museum-goers might see, I think of the Gee's Bend quilts and the AIDS quilts, of the first International Women's March, the objects left at the Vietnam Memorial and on the graves of Iraq War soldiers. The historical events all differ but recognition of the need to memorialize is always strong.

What a beautiful story! Thank you, Susan. With your words you have also saved the memory of your grandmother and her knitting.