The Shetland Islands

Scotland

2013

One summer evening a hundred miles north of mainland Scotland, I stood bundled and braced against the North Atlantic wind, shoulder to shoulder in a circle with 82 other knitters. Together, we formed a continuous loop of knitters and knitting 200 feet across. Gusts of wind tossed swirls of hair against my face, damp with the aroma of sea air. I shivered. It was cold for August, even in the Shetland Islands.

We knitters were on the lawn beside the historic Bød of Gremista near the Hanseatic burgh of Lerwick, within sight of the harbor with fishing boats and the NorthLink Ferry to Aberdeen. Swedish artist Kerstin Lindström had created our circle using 83 rectangular panels, each panel measuring about one by three feet. Members of the knitting network Gavstrik in the Faroe Islands had knitted the panels that Kerstin joined together with knitting needles on flexible connectors to create our continuous loop. One wooly red panel lay on the grass in front of each knitter.

Knitters needed only to know the basic knit stitch and be able to stand for one hour to join the circle. Each of us was either a local Shetlander drawn by a call in the Shetland Times newspaper or an outsider, like me, on the island to attend In the Loop, an international and interdisciplinary conference with a Nordic focus held at the Mareel and the Shetland Museum and Archives in Lerwick. The conference connected heritage knitters and scholars of knitting history during three days of paper presentations and social events on the culture, education, business, design, and art of knitting.

Kerstin titled her artwork Own Our Own Time. She wanted to see, feel, and understand the human pace of time preserved with knitting. The circle of knitters formed a sculpture on the Shetland landscape, a circle that brought knitters together to experience Monumental Knitting.

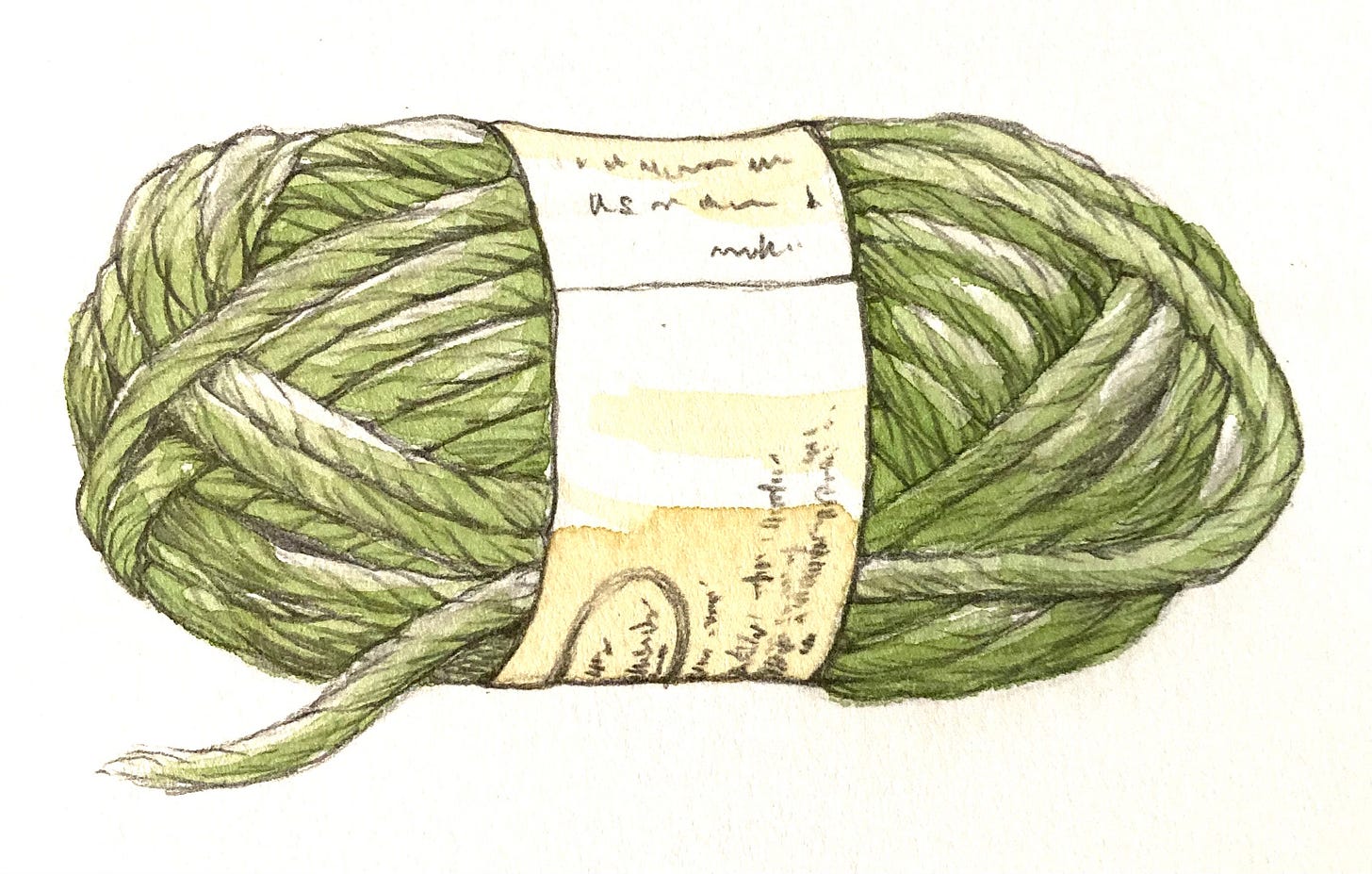

“Wait for my signal, then remove the rubber band from your needles and pick up your panel,” Kerstin called from within the circle. “Each of you will be given a ball of yarn.” The moss green yarn was the kind donation of Jamieson & Smith Shetland Wool Brokers in Lerwick. “Wait for my signal to start knitting. Everyone starts at the same time. We will knit plain rows for one hour.”

The slowest knitters set the pace, unusual in a digital age of speed for its own sake.

“While you are knitting . . . or waiting to knit,” she said. “You may want to reflect on this question.” She paused and looked around the circle.

“When do you own your own time?”

I’ll get back to you if my academic life allows time for such self-indulgent contemplation, I thought. My skepticism took me by surprise. Later in life, I had returned to graduate studies and then worked my way to tenure as a professor of historical and cultural textiles, each day packed with students and lectures, grading and advising, meetings and committees, research and writing, travel and presentations. I took pride in how hard I worked. Odd, that. A wave of regret for my skepticism washed over me, and I nodded toward Kerstin with my most mindful and attentive expression.

Kerstin called for us to begin knitting. I picked up the panel and needles in front of me, removed the rubber band from the needles, accepted my ball of yarn, and bent my head toward my stitches. I knitted across one row, ready to slide my knitting to the person on my left and to accept the next panel from the knitter on my right.

My brow furrowed over my imperfect understanding of Own Our Own Time.

When did I own my own time?

For one thing, I thought, I own my own time when I knit. The yarn, the patterns, the time set aside to knit on my own or with others—I own that.

Streams of gentle chatter drifted about the circle. The knitter to my left—a journalist on assignment—frowned at the wooly green stitches she worried through each loop. “I haven’t knit for a long time. I am slow,” she whispered to me in her soft Shetland accent. A sudden gust blew her long dark hair across her face. She swept back the strands and her knitting nearly fell from her hands.

“My hands are cold. And this knitting, I can’t sprett this knitting,” she said.

“Sprett? What does sprett mean?” I asked.

“I can’t unravel my knitting. I can’t fix mistakes. In Shetland, when things don’t go right, we say they sprett, they unravel.” The word sprett held a lingering Nordic influence on the Old Scots dialect of Shetland.

“In the States, we call it frogging,” I told her. “You make a mistake, you rip it. Rip-it, rip-it, rip-it.” I also told her about our UFOs—unfinished objects—and our LYS—local yarn shop. We shared a laugh, two strangers having fun with the language of knitting.

The knitter to my right zipped across her row of knitting and glanced toward me, impatient with the slow pace. She handed me her knitting, stepped behind me outside the circle, tapped the slow-knitting Shetlander’s shoulder, asked for her knitting, made short work of knitting across her row, handed the knitting back to her, and returned to her place on my right. She was not on board with waiting. She owned her own time. My Shetland acquaintance thanked her—how gracious—and picked up her pace of knitting, her stitches less perfect.

I knit across one panel after another. The warmth of wool sliding through my fingers relaxed into the familiar rhythm of throwing and looping yarn. My mind drifted to my other experiences with Monumental Knitting, times when I knit in the company of many knitters.

The Sock Summits!

The August 2009 Sock Summit, a gathering in Portland, Oregon, had been all about knitting socks, and I was among 937 knitters who broke the Guinness World Record for Most People Knitting Simultaneously. The previous record was held by 236 Australian knitters, and our record in Portland would be shattered in 2012 by 3,083 British knitters at Royal Albert Hall.

We knitters—soon-to-be record-breakers—brought our yarn and mandatory single-pointed straight needles to the main ballroom of the Oregon Convention Center. We handed in our venue tickets at the entry door to document the number of knitters. Then the doors were locked, and we knitted for a closely timed 15 minutes. Strict start and end times were called. (Very particular, the Guinness folks.)

All told, Sock Summit 2009 hosted some 1,500 student knitters, 40 workshop teachers, and 150 vendors—all with a thing for knitting socks.

There was, of course, a sock hop.

Two years later, at the July 201l Sock Summit, also in Portland, I had hurried from my classroom with hundreds of other knitters to form a flash dance mob. We clutched our beloved skeins of yarn (no needles, wisely) and broke into song on the terrace outside the Oregon Convention Center. Led in choreographed jumps, bends, and twirls—not unlike mating dances among migratory sandhill cranes—we bopped in sync to “I’ve Had the Time of My Life.” Traffic slowed. People on a passing bus stood up for a better look. Pedestrians nudged one another, stopped, pointed. Onlookers gathered and stared. The music ended and we flash dance knitters cheered with joy and tossed colorful skeins that flew in the air like a celebratory tumble of mortarboards.

Compared with exuberant Monumental Knitting at Sock Summits, Own Our Own Time in Shetland was quiet, rather Nordic, I thought. Perhaps the cold subdued us.

We knit for one hour and Kerstin called a halt. She and a helper gathered the knitted panels, knitting needles, and yarn into a surprisingly compact bundle. There would be future performances of Own Our Own Time—using locally sourced yarn—in France, Canada, Sweden, and Iceland.

“Together, our knitting has saved a piece of unforgettable Shetland time,” she said.

Clusters of knitting friendships, old and new, set off to find the nearest warm places. At a pub in Lerwick, I held my chilly fingers to an open fireplace. Staring into the flames and flickering shadows on the hearth, my thoughts wandered to Kerstin’s words about knitting and time.

I remembered my first knitting mentor, decades earlier, who had advised, “Knitting will give you something to show for your time.”

Kerstin and my mentor were right.

Knitting had preserved my time and stories from a lifetime of knitting. A garter stitch dishcloth held the story of childhood knitting lessons with my Danish grandmother. My first cardigan showed a teenaged me, an anxious girl who escaped into knitting. Knitted mittens and yarn of other cultures spurred my intellectual curiosity and led to far-flung ventures.

And in the summer of 2013, three rounds of Jamieson’s moss green wool preserved forever my time in Shetland within the circle of knitters.

This post is a reprint from Susan Strawn’s new Substack page called “Susan’s Substack.” She is both writer and illustrator. She presents a fabulous story of her journey around the world through knitting. Please support her page through a paid subscription if you can. Recommend her and share her column with friends.

Emerging Voices is pleased to be a part of The Iowa Writers Collaborative. Check us out through our Sunday Round-Up or Wednesday Flipside. You’ll find writers to love at this link:

I love this story, makes me want to re-learn to knit or at least find some way to own my time. My mother was a skilled knitter and made everyone beautiful sweaters. My mother-in-law was a happy, sloppy knitter and made everyone over-size, shapeless (no heel) but very warm socks! Here is to them and to you, Susan.

This is wonderful!