On these early summer mornings, I work in our small garden plot, a sunny patch of earth right beside our 100-year-old home in Muscatine, Iowa. A few weeks earlier, on Mother’s Day, my husband and I planted sturdy seedlings deep into the soil to promote a strong root base. We set cages around four varieties purchased from a favorite vendor at our downtown farmers market: Celebrity, Early Girl, Brandywine Pink and Amana Orange. We anticipate a colorful harvest. This morning as I pinch off emerging side shoots, I am carried by the bright, leafy green aroma back to my uncle’s garden in New Jersey.

Paid subscribers will find a link at the bottom of this page to Friday’s 6/28/24 Office Lounge at noon.

Listen to this essay read by the author:

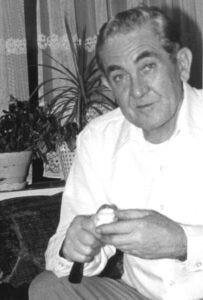

My uncle was a master electrician. But I remember my Uncle Victor as a magician.

At family celebrations, he would entertain us with his sleight of hand. He could make a coin appear from behind a child’s ear. And in another trick, my uncle’s thumb strikes the red tip of a wooden matchstick, the sulfur sizzling as it bursts into flame. The children, entranced and motionless, watch the flame descend as the wood burns, turns charcoal black, and curls downward. Just before the flame reaches his thumb and forefinger, my uncle, with a sharp breath, blows it out.

Then he reaches with his right hand and pretends to pluck a strand of hair from a child’s head. With great concentration, he winds that imaginary strand around and around the blackened match. With a quick tug on that invisible hair, the tip of the match snaps off, arcs in the air, and lands on his clean white cotton handkerchief spread like a safety net over my aunt’s lace tablecloth. It took me years to figure out that my uncle achieved this bit of trickery by flicking the base of the match held in his left hand while diverting our attention with a flourish of his right.

As I stand in my sunlit garden and breathe in the warm, grassy fragrance of tomato leaves that stain my fingers yellow, I realize that the real magic in my uncle’s hands was his green thumb, his ability to plant and tend a garden that year after year would yield bountiful crops of crisp cucumbers, crunchy kohlrabi, and tasty tomatoes.

Growing, I would often walk to the upper mountain home of my aunt and uncle to play with my two younger cousins. My memories of those days are like fading snapshots jumbled together in an old shoebox. I am determined now to write a description on the back of each and every one.

March. The seeds my uncle saved from the most flavorful tomatoes of last season’s harvest sprout in potting trays set on the wide sill of the dining room’s south-facing picture window.

Given the right conditions, not unlike these tender seedlings, the story of my uncle’s young life slowly emerges from the depths of closely guarded family memories.

My uncle, born in Ukraine, was the third of four children. His parents were German citizens even though they were both born in Neu Danzig, a village nestled in the Ingul River Valley in the Mikolaivs’ka Province of Ukraine. This settlement of German farmers and tradespeople was one of many such villages established in the late 18th century when, after her army’s victory in the Russo-Turkish War against the Ottoman Empire, Catherine the Great invited foreign settlers to cultivate the vast steppes in the Black Sea region.

My grandmother always laughed heartily whenever she told us the story of the anticipated birth of her third child. Her husband, already the father of two healthy sons, dearly hoped for a daughter. When this quiet and gentle man received news of the birth of a third son, my grandfather, in a rare display of ill temper, was said to have grabbed the wool cap from his head and thrown it to the floor. He need not have worried. His wish for a daughter was fulfilled two years later with the birth of my mother, Nelly.

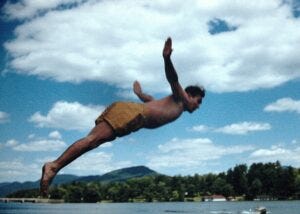

Uncle Victor, like his older brothers Alexander and Karl, loved sports, especially soccer. The three brothers were inseparable and had a reputation for standing up for one another and for their family.

As a school girl, my mother would wear her thick brown hair in two long braids. A smitten classmate, hoping to get her attention, tried to dip the end of one braid into the inkwell in his desk. His friends dissuaded him by revealing the identity of her older brothers. They chanted the refrain, “Die Brüder Schmidt sind immer zu dritt.” Everyone knew that if one brother felt the need to answer a challenge or uphold the honor of his family, the offender would have to reckon with all three brothers.

My uncle’s idyllic childhood all too soon would be shattered when on June 22, 1941, Hilter invaded the Soviet Union. In a swift and brutal response, Joseph Stalin ordered the arrest of all male German citizens of military age. In the early hours of the next morning, Uncle Victor’s father and two brothers were taken from their home. My grandfather was 48 years old. My two eldest uncles were 20 and 18. They were never seen again.

Year after year, my grandmother, with the help of my mother, sent inquiries about her husband and sons to government agencies and humanitarian organizations. In one such letter, dated February 1954, to the Department of the Next of Kin of the Fallen of the Former German Forces, my grandmother wrote, “Now that so many HeimKehrer (homecomers) are being released and returning to their homes, I am hoping to one day receive news of the whereabouts of my husband and my two sons who were arrested and carried off by the NVKD,” the Soviet Secret Service.

May. My uncle plants rows of tomatoes and cucumbers in his garden, a large plot of loamy soil enclosed by a tall green metal fence.

In 1945, after a three-year journey northeast through Ukraine, Poland and Germany, my grandmother, my uncle and my mother arrived at the home of the widow of my grandmother’s brother in Hamelin.

There, Uncle Victor met Gerda Gohr, a lovely young woman with rich auburn hair who worked as an usherette at a movie theater. My uncle was attractive with jet black hair, piercing blue eyes and a disarming smile. Although he was not very tall, only five foot, eight inches, my uncle had a lean, athletic frame. He possessed a self-assured grace on the dance floor. My mother often recalled, with no small amount of pride, when she and her brother won first prize for the samba in a dance competition–a magnum of champagne.

June. I open the narrow metal gate and wander into my uncle’s garden. Uncle Victor, sitting on an overturned bucket, weeds a long, straight row of bright leafy plants and vines. He invites me to help him tend his tomato plants. He teaches me to pinch off the tender shoots growing between the main stem and the lateral branches. The herbal scent fills the air around us.

This pruning, he explains with his kind and patient manner, helps the plants direct energy to producing more fruit. And this judicious removal of foliage improves airflow to prevent diseases and allows sunlight to reach the fruit to help them ripen.

As a young man, Uncle Victor took after his father who designed icebreaking steamers that navigated the Northern Sea Route and the Arctic Ocean, and his grandfather who, as a furniture maker, carved church pulpits, altars and statues. Uncle Victor was mechanically inclined, skilled with machines and vehicles. And having grown up in the city of Nikolayev, he knew very little about farming. Gerda’s parents owned a small farm just outside of Hamelin across the Weser River. Every Sunday, Gerda’s parents brought fresh produce and flowers to the market square. Before he could afford a horse, Gerda’s father pulled the cart to the market himself.

After they were married, Victor and Gerda worked alongside her parents on the farm, growing mainly potatoes and beets. Victor learned from his father-in-law Albert how to prepare the soil and select seeds to yield the best harvest.

On early summer mornings, Gerda laid out a blanket on a hillside near the road into town, and with her first-born son toddling nearby, she sold fresh strawberries.

August. My uncle invites me to sit with him at the kitchen table. He spreads a generous hunk of liverwurst bought at the German Schlachter onto dense dark pumpernickel bread. He feathers rings of a sharp onion over the seasoned pork spread and tops the open-faced sandwich with a thick slice of one of his sun-ripened tomatoes. He pours two fingers of his Budweiser into a small jelly jar and sets it beside the plate he has prepared for me. Looking around the bright kitchen with its yellow beadboard cabinets, I wonder at the strength, courage and faith of my family to twice leave everything behind and start over in hope of a better future for themselves and their children.

Victor and Gerda sailed with their 6-year-old son on the SS America from Bremerhaven, arriving eight days later at Ellis Island on March 10, 1954. Together, they were the caretakers of the First Evangelical United Brethren Church in Newark, New Jersey. The young family of three lived in the apartment above the Sunday School classrooms.

In 1961, my aunt and uncle bought a three-family home in Montclair, New Jersey. My eldest cousin remembers helping his father dig a 6-foot wide by 12-foot long by 12-foot deep hole in the front yard to install an underground oil tank.

Every day after high school, my cousin Axel would fill a red metal wheelbarrow and cart away the dirt. His 5-year-old brother helped by gleefully riding atop each load, down the long, steep driveway to the backyard.

Uncle Victor worked as an electrician at Royal Plating and Polishing in Newark. A few years later, when the company moved to Edison, Uncle Victor made the nearly 60-minute commute morning and evening. For eight hours every weekday, he worked over hot machines. After his long commute home, Victor joined his son in digging and moving the dirt and rock in order to save money. After the oil tank was installed in the front yard, father and son turned leaves and soil into a fertile backyard garden.

Year after year, the family enjoyed an abundant harvest of vegetables. In addition to the fresh-from-the-garden taste of crisp cucumbers and ripe tomatoes, I remember my uncle’s wise words and thoughtful advice.

Sitting at the kitchen table, I look up at my uncle. Something has been weighing on my mind. My uncle has always been able to fix broken toys, repair damaged tools, and patch plaster walls. Trusting that he will ease a troubled mind, I share my problem with him. Walking home from school, I caught up to a friend who was chatting with another classmate. When I greeted them, the classmate turned away and tugged on my friend’s arm. To my surprise, she followed without looking back.

My uncle takes a moment to look out the window. He draws in a deep breath and sighs before returning his gaze to me. His expression is kind, but a little bit tired and sad.

“Annettchen. You should not think so long on the way others behave.” He places his large hand over mine and pats it gently. “Think only about how you behave, how you treat others. That is most important, ne?”

When my uncle smiles at me, his eyes crinkle in the corners and I can’t help but smile back. My mind at ease, I realize I am hungry so I raise the open-faced sandwich to my lips.

Before I can take a bite, Uncle Victor raises a finger directing me to wait just one moment. Rising from his chair, he retrieves a plate of fresh cucumber wedges from the Kühlschrank, a single-door refrigerator in harvest gold. Returning to the table, he tips a glass shaker filled with a mixture of salt and white rice, and seasons two seed-capped, pale green wedges before setting them on my plate.

Satisfied, my uncle turns his gentle blue eyes to me and nods. He waits until I take a bite and smile up at him before he settles back in his chair to enjoy his meal in companionable silence.

Back in my garden, I carve a moat around each tomato plant and water each one slowly and deeply at its base, just like my uncle taught me. I mulch around the plants with a thick layer of dry grass clippings.

Tending a garden is quiet work. In the cool early morning stillness, I set a row of basil in front of the tomato plants. I will add two rows of orange and yellow marigolds before watering in all the new plants.

A chickadee lights on a branch of the dogwood tree just above the birdbath. Its sweet call reminds me to fill the concrete basin with fresh, cool water. This energetic bird flits from branch to branch higher into the gently unfolding green canopy and watches my progress.

“Heirloom Tomatoes” was first published in Roads We’ve Taken: A Writers on the Average Anthology, June 2023 by Pearl City Press, Muscatine, Iowa.

Copyright © 2023 by Annette Matjucha Hovland, then in The Blazing Star Journal, 2024.

Art credit: Annette Matjucha Hovland.

Photo credits: Nils Alexander Hovland, Ippolit Matjucha, Gerda Gohr Schmidt, and Foto-Thüring, Hameln, Osterstraße 38

Annette Matjucha Hovland is an artist of many mediums. She is a poet, a journalist, a photographer and a teacher. A native of New Jersey, she currently lives in Muscatine, Iowa.

Mary Swander’s Emerging Voices is happy to be a part of the Iowa Writers Collaborative. Check out columns by its members every week in the Sunday Round-Up:

https://us06web.zoom.us/j/82824062374?pwd=sMp3H7aEcBLXbBxIsLZ6sWVIXowIXr.1

Poignant, heartbreaking and lifting, beautiful.